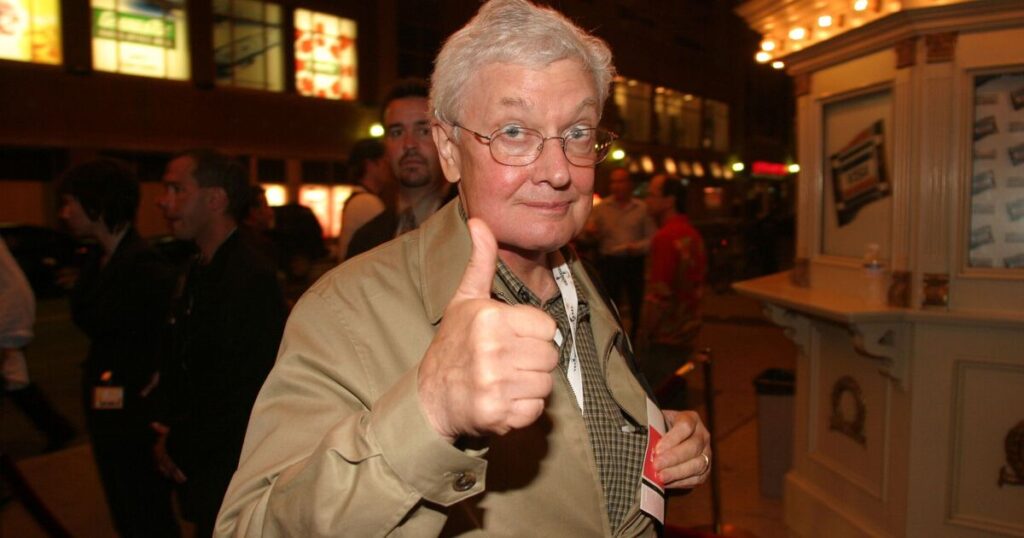

Renowned film critic Roger Ebert was one of the most notable voices in cinema. He was the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize Award and he shared his views and passion for movies in an accessible and engaging way. He was first and foremost a fan of film before a critic and this was reflected in his writing.

Just one year before his death in 2013, Ebert decided to share a list of his favourite films to share with the British Film Institute for their popular Sight & Sound poll.

Notorious

First up is 1946’s Notorious, on the film Ebert said: “I do not have the secret of Alfred Hitchcock and neither, I am convinced, does anyone else. He made movies that do not date, that fascinate and amuse, that everybody enjoys and that shout out in every frame that they are by Hitchcock. In the world of film he was known simply as The Master. But what was he the Master of? What was his philosophy, his belief, his message? It appears that he had none. His purpose was simply to pluck the strings of human emotion — to play the audience, he said, like a piano. Hitchcock was always hidden behind the genre of the suspense film, but as you see his movies again and again, the greatness stays after the suspense becomes familiar. He made pure movies.

“Notorious is my favourite Hitchcock, a pairing of Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman, with Claude Rains the tragic third corner of the triangle. Because she loves Grant, she agrees to seduce Rains, a Nazi spy. Grant takes her act of pure love as a tawdry thing, proving she is a notorious woman. And when Bergman is being poisoned, he misreads her confusion as drunkenness. While the hero plays a rat, however, the villain (Rains) becomes an object of sympathy. He does love this woman. He would throw over all of Nazi Germany for her, probably — if he were not under the spell of his domineering mother, who pulls his strings until they choke him.”

Raging Bull

“Ten years ago, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver was on my list of the 10 best films. I think Raging Bull addresses some of the same obsessions, and is a deeper and more confident film. Scorsese used the same actor, Robert De Niro, and the same screenwriter, Paul Schrader, for both films, and they have the same buried themes: A man’s jealousy about a woman, made painful by his own impotence, and expressed through violence,” said the film critic.

He added: “Some day if you want to see movie acting as good as any ever put on the screen, look at a scene two-thirds of the way through Raging Bull. It takes place in the living room of Jake LaMotta, the boxing champion played by De Niro. He is fiddling with a TV set. His wife comes in, says hello, kisses his brother, and goes upstairs. This begins to bother LaMotta. He begins to quiz his brother (Joe Pesci). The brother says he don’t know nothin’. De Niro says maybe he doesn’t know what he knows. The way the dialog expresses the inner twisting logic of his jealousy is insidious. De Niro keeps talking, and Pesci tries to run but can’t hide. And step by step, word by word, we witness a man helpless to stop himself from destroying everyone who loves him.”

The Third Man

Ebert said: “This movie is on the altar of my love for the cinema. I saw it for the first time in a little fleabox of a theater on the Left Bank in Paris, in 1962, during my first $5 a day trip to Europe. It was so sad, so beautiful, so romantic, that it became at once a part of my own memories — as if it had happened to me. There is infinite poignancy in the love that the failed writer Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) feels for the woman (Alida Valli) who loves the “dead” Harry Lime (Orson Welles). Harry treats her horribly, but she loves her idea of him, he neither he nor Holly can ever change that. Apart from the story, look at the visuals! The tense conversation on the giant ferris wheel. The giant, looming shadows at night. The carnivorous faces of people seen in the bombed-out streets of postwar Vienna, where the movie was shot on location. The chase through the sewers. And of course the moment when the cat rubs against a shoe in a doorway, and Orson Welles makes the most dramatic entrance in the history of the cinema. All done to the music of a single zither.”

28 Up

Next up was 1984’s 28 Up, Ebert said: “I have very particular reasons for including this film, which is the least familiar title on my list but one which I defy anyone to watch without fascination. No other film I have ever seen does a better job of illustrating the mysterious and haunting way in which the cinema bridges time. The movies themselves play with time, condensing days or years into minutes or hours. Then going to old movies defies time, because we see and hear people who are now dead, sounding and looking exactly the same. Then the movies toy with our personal time, when we revisit them, by recreating for us precisely the same experience we had before. Then look what Michael Apted does with time in this documentary, which he began more than 30 years ago. He made a movie called “7-Up” for British television. It was about a group of British seven-year-olds, their dreams, fears, ambitions, families, prospects. Fair enough. Then, seven years later, he made 14 Up, revisiting them. Then came 21 Up and, in 1985. 28 Up, and next year, just in time for the Sight & Sound list, will come 35 Up And so the film will continue to grow… 42… 49… 56… 63… until Apted or his subjects are dead.

“The miracle of the film is that it shows us that the seeds of the man are indeed in the child. In a sense, the destinies of all of these people can be guessed in their eyes, the first time we see them. Some do better than we expect, some worse, one seems completely bewildered. But the secret and mystery of human personality is there from the first. This ongoing film is an experiment unlike anything else in film history.”

2001: A Space Odyssey

Last up is 2001: A Space Odyssey, Ebert explained: “Film can take us where we cannot go. It can also take our minds outside their shells, and this film by Stanley Kubrick is one of the great visionary experiences in the cinema. Yes, it was a landmark of special effects, so convincing that years later the astronauts, faced with the reality of outer space, compared it to ‘2001’. But it was also a landmark of non-narrative, poetic filmmaking, in which the connections were made by images, not dialog or plot. An ape uses to learn a bone as a weapon, and this tool, flung into the air, transforms itself into a space ship – the tool that will free us from the bondage of this planet. And then the spaceship takes man on a voyage into the interior of what may be the mind of another species.

“The debates about the “meaning” of this film still go on. Surely the whole point of the film is that it is beyond meaning, that it takes its character to a place he is so incapable of understanding that a special room – sort of a hotel room – has to be prepared for him there, so that he will not go mad. The movie lyrically and brutally challenges us to break out of the illusion that everyday mundane concerns are what must preoccupy us. It argues that surely man did not learn to think and dream, only to deaden himself with provincialism and selfishness. ‘2001’ is a spiritual experience. But then all good movies are.”