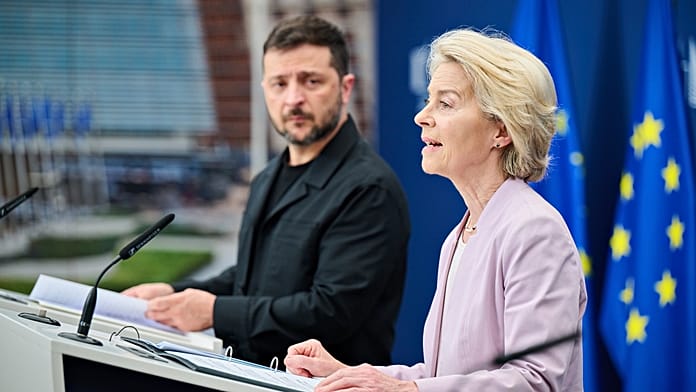

Ursula von der Leyen has implored European Union countries to agree by December on a plan to cover Ukraine’s military and financial needs for the next two years, estimated at a staggering €135.7 billion, according to a letter sent on Monday and seen by Euronews.

“It will now be key to rapidly reach a clear commitment on how to ensure that the necessary funding for Ukraine will be agreed at the next European Council meeting in December,” the European Commission President wrote to the 27 leaders.

“Clearly, there are no easy options,” she added in the letter.

“Europe cannot afford paralysis, either by hesitation or by the search for perfect or simple solutions which do not exist.”

In the document, von der Leyen highlights the “particularly acute” scale of funding that Ukraine will require in 2026 and 2027: €83.4 billion to fund the Ukrainian army and €55.2 billion to stabilise the economy and address the budget deficit.

Her assessment draws from estimates by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Kyiv’s authorities, and it is based on the assumption that Russia’s full-scale war will end in late 2026, even if that is by no means certain. A ceasefire, seen as a precondition for a peace agreement, remains elusive.

The letter details the three main options to support Ukraine.

- €90 billion in bilateral contributions by member states. The assistance would be disbursed as a non-repayable grant and be accounted against a member state’s national budget, including any associated interest payments.

- €90 billion in joint debt. The interests would have to be covered by either national guarantees or the bloc’s common budget. Amending the budget’s legislation would require unanimous approval, a tall order given Hungary’s opposition to funding Ukraine.

- €140 billion in a reparations loan based on Russia’s immobilised assets. Kyiv would be asked to repay the loan only after Moscow agrees to compensate for the damages.

The first two options, she notes, would increase the fiscal burden, as the financial aid would come from either a direct cash contribution from a member state or fresh money raised on the markets.

The third option, the reparations loan, avoids this scenario as it would incur extra expenses, fresh debt or impact national budget contributions. Instead, it would use the cash balances generated by the immobilised assets of the Russian Central Bank, the bulk of which is kept at Euroclear, a central securities depository in Brussels.

Facing potential legal ramifications, Belgium is the main hold-out.

The country has demanded maximum legal certainty and total burden-sharing to defend itself against Russia’s retaliation if Moscow were to sue. In her letter, von der Leyen acknowledges the risks and warns of “potential knock-on effects”.

Von der Leyen met Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever last Friday to advance the talks, which have so far yielded limited progress.